- Home

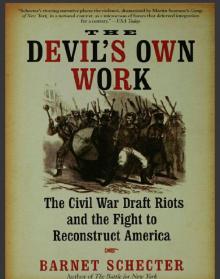

- Barnet Schecter

The Devil's Own Work Page 2

The Devil's Own Work Read online

Page 2

July 1-3: Union victory at Battle of Gettysburg; Lee retreats

July 4: Confederate surrender of Vicksburg to Ulysses S. Grant

July 13-18: Draft riots in New York City; blacks targeted; violent resistance in Boston and across the North; black troops martyred in Union assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina

September: Lenient prosecution of rioters; rise of William "Boss"

Tweed in New York; Confederate victory at Chickamauga, Tennessee

November: Union victory at Chattanooga, Tennessee

1864 May-August: Grant fights his way toward Petersburg and Richmond

August: Confederate attempt to start riots in Chicago

September: William T. Sherman's Union forces capture Atlanta

November: Lincoln reelected; Confederates try to burn New York

1865 January: Thirteenth Amendment abolishes slavery in the U.S.

April: Grant captures Richmond, war ends; Lincoln assassinated, succeeded by Vice President Andrew Johnson

1866 Riots in Memphis and New Orleans, African Americans massacred; Fourteenth Amendment grants citizenship to African Americans

1867 Reconstruction Act of 1867 puts the South under martial law and helps establish new state governments with participation of blacks

1868 Emergence of Ku Klux Klan; Grant elected president (Republican) over the Democratic candidate, Horatio Seymour, former governor of New York.

1870 Fifteenth Amendment grants voting rights to blacks throughout U.S.

1871 Orange Day riot between Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants in New York City; fall of the corrupt Tweed "Ring"

1872 Grant reelected over the Liberal Republican candidate, and New York Tribune editor, Horace Greeley

1873 America's first "Great Depression" begins; massacre of black militia by White League in Colfax, Louisiana

1874 Escalation of anti-black, anti-Republican violence in the South; northern willingness to intervene with federal troops declines

1876 Disputed presidential election between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden

1877 Hayes wins the White House; withdrawal of federal troops from the South ends Reconstruction; nationwide railroad strike and riots

Prologue: " We Have Not One Devil,

But Many to Contend With"

ar more important than all military events, & more disastrous, & still more ominous of evil for the North than would be a signal defeat on a battlefield, is the occurrence of a wide-spread & bloody riot in the city of New York," the Virginia secessionist Edmund Ruffin exulted in his diary on July 18, 1863. The nation's first federal conscription, which exempted those who could pay three hundred dollars, triggered the worst riots in American history, which spread from New York to neighboring areas, including Westchester County, Long Island, Staten Island, and Jersey City, as well as Newark and Troy. Violent resistance to the draft had erupted throughout the Union, from the marble quarries of Vermont and the Pennsylvania coalfields to the midwestern states of Ohio, Indiana, Iowa, and Minnesota.1

Ruffin, like many southerners, clearly hoped the riots would counteract the stunning Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, which had thwarted General Robert E. Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania two weeks earlier, on July 1-3, 1863. Gettysburg, and the fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 4, together marked the great turning point of the Civil War, setting the Union on the path to final victory after two years of almost unrelieved failure on the battlefield. The riots were over by the time Ruffin took note of them, but he hoped the forced suspension of the draft in New York City would encourage renewed outbursts across the North.2

In his 1860 novel, Anticipations of the Future, Ruffin envisioned the destruction of New York by riot and arson, along with an alliance between the South and the Midwest, as the keys to victory over the North in a civil war. The slave states would win their independence, Ruffin predicted, because the disruption of trade with the agricultural South would trigger business failures and rampant unemployment in Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and other northern cities.

Edmund Ruffin

In the grim certainty of the past tense, Ruffin's narrator described angry workers in New York raiding gun shops and liquor stores, defeating the police and military, and torching buildings all over the city. "A strong wind was blowing, which soon spread the flames faster than did the numerous incendiaries." New York and Brooklyn and their suburbs became "one raging sea of flame . . . rising in billows and breakers above the tops of the houses higher than ever sea was raised by the most violent hurricane," Ruffin wrote. "Many thousands of charred and partly consumed skeletons . . . were afterwards to be seen among the ruins." The South repelled the northern invaders and captured Washington, D.C., which became the seat of the southern federal government; the novel ended with a truce between the two sides, and the prospect of the midwestern states breaking away from the North to ally with the South.3

By July 1863, Ruffin seemed clairvoyant. Union forces had suffered so many defeats since the Civil War began in April 1861 that the Confederate States of America seemed on the verge of becoming and remaining a separate, slaveholding republic. New York was burning, and since late June, some 2,500 Confederate cavalrymen led by the bold and reckless John Hunt Morgan had been trying to destabilize the Midwest: Invading from northern Kentucky, the raiders had been tearing through Indiana and Ohio, hoping to spark an insurrection among the disgruntled inhabitants.4

Perhaps the Confederate leadership in Richmond was using Ruffin's novel, along with remarks in a similar vein by southern orators and newspaper editors, as a blueprint for its military strategy: Combined with Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania in early July, and with the raid in the Midwest, the riots in New York and other cities struck alarmed northerners as part of a concerted plan. That Lee's invasion had stripped New York of its militia, who were rushed to Pennsylvania two weeks before the riots, likewise fueled this suspicion.

The New York Times declared on July 16: "When the plots of the Southern rebels for the overthrow of the Union and the inauguration of war first took form and shape, one of the great elements of power and success upon which they counted was the cooperation of the 'New-York mob,' or the 'Northern mob.' This mob, these masses of the great industrial centres of the North were, in fact, at one time looked upon as the chief tool in the hands of the Secessionists." The Times was convinced that "agents direct from Richmond" were in the city "using both energy and money in feeding the flames that for three days have darkened, and for three nights have reddened, the sky of New-York." None of these conspirators had been identified, the Times explained: "As a matter of course, they work under false pretexts and with devilish subtlety."5

The riots that broke out in New York on July 13, 1863, appeared to be a spontaneous popular uprising against Abraham Lincoln's imposition of the nation's first federal draft and its clause exempting any conscript who could provide a substitute or pay three hundred dollars, which amounted to a year's wages for many workingmen. The Times assumed the true "instigators" of the riot were "holding themselves prudently in the background," since "no distinct individual leadership" was discernible among the mobs.6 Triggered by the sacking and burning of a draft office at Forty-sixth Street and Third Avenue on a Monday morning, the riots quickly escalated into four days of looting, arson, and lynching that left more than one hundred known dead, forced thousands of African Americans to flee the city, and threatened to destroy the Union's commercial and industrial hub.7

The strongest evidence against the conspiracy theory is that the Confederates could not re-create the draft riots in the North even though they tried for the rest of the war, using agents based in Canada. The explosive mix of ingredients in 1863 was too complex to replicate at will. Layered with elements of racial, religious, ethnic, and class conflict, the draft riots, as they were known, were about much more than the draft. And the scale of the fighting across the entire metropolitan area—with platoons of troops using live ammunition and artillery r

ounds—went beyond most riots. In the words of the city's ineffectual mayor, George Opdyke, the draft riots were a "civil war" in which citizen volunteers had to be enlisted against their rioting neighbors because the police and military were overwhelmed.8

The rioters took encouragement from earlier speeches by New York's Democratic politicians, including Governor Horatio Seymour and Congressman Fernando Wood, who sympathized with the slaveholding Confederacy and attacked the Lincoln administration for using the war as an excuse to encroach on northerners' civil liberties. Poor, white, and largely Irish Catholic rioters clashed with policemen and soldiers, many of whom were also Irish. The mobs targeted the homes of wealthy, native-born Protestants, who tended to be Republicans, and who appealed to Lincoln for federal troops to crush the immigrant rioters and execute their demagogic leaders. Blacks, resented by poor whites as competitors for jobs and as the favored minority of Republican abolitionists, were attacked wherever they could be found.9

Black leaders saw the Democrats and their newspapers as the true culprits. For years, physician James McCune Smith explained, "the press, with but few exceptions, hounded on the increasing hatred of the multitude until it found logical expression in the unspeakable atrocities of the New York riots." Fighting the battle in the press, Manton Marble, editor of the New York World and spokesman for the Democrats, defended the rioters and excoriated the Lincoln administration for its military "despotism." Marble also locked horns with Horace Greeley, the Republican editor of the New York Tribune, who had pressured Lincoln to abolish slavery and came to be identified with the radical wing of the party during the Civil War, making him and the Tribune office prime targets for the mobs.10

Indeed, this civil insurrection was a microcosm—within the borders of the supposedly loyal northern states—of the larger Civil War between the North and South. Enmeshed in the fight over the government's new conscription law were the very issues—of slavery versus freedom for African Americans, and the scope of federal power over states and individuals—that had shattered the country and plunged it into years of sectional strife. And the riots themselves prefigured a backlash against the abysmal living and working conditions of America's underclass that turned the rest of the nineteenth century into the most violent period of labor conflict in American history.11

• • •

The rioters' rage stemmed as much from the draft as from Republican president Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which went into effect six months earlier, on January 1, 1863, declaring all slaves in the rebellious states to be "thenceforward and forever free." To fulfill this promise of freedom, Union forces would not only have to win on the battlefield but take over the South and implement a social revolution. Democratic leaders, particularly Fernando Wood, had been telling their working-class constituents for years that free blacks from the South would take their jobs; with the Emancipation Proclamation, they warned, the federal government was sending them to die for the slaves who would replace them on the docks and in the factories.12

The Emancipation Proclamation can be seen as the first act in the contentious process of Reconstruction, a struggle to determine not only the proper treatment of the vanquished Confederate states after the war but the legal and social status of African Americans as well. Thus Reconstruction in effect began during the war, even as northerners clashed over how it should end. Radical Republicans wanted to fight on until the South was conquered and slavery was overthrown, after which they intended to raise the former slaves to full equality. Conservatives, mostly Democrats, hoped instead to end the war either by negotiation or by a limited military victory that would reunite the country without reconstructing southern society and leave slavery intact.13

New York City, with its strong commercial ties to the South, was a hotbed of sympathy for the Confederates, overrun, according to "loyal" northerners, by traitorous Democratic "Copperheads," named after the poisonous snake, who demanded negotiation, lenient treatment of the Confederates, and preservation of their social structure through whites-only local self-government, referred to as "home rule." New York's radical Republicans—civic leaders like Joseph Choate, George Templeton Strong, and Frederick Law Olmsted—aided the black victims of the draft riots and urged Lincoln to impose martial law as a way to end the violence and purge the city's corrupt, "semi-loyal" officials. By contrast, the Democrats who ran the city—William Tweed, A. Oakey Hall, John Hoffman, and a host of aldermen and state senators—countered that they as local leaders were best suited to calm the mob's fury through negotiation and to cope with the aftermath of the crisis.14

Thus not only were the draft riots a microcosm of the Civil War, but the debate over how to end the riots and dispense justice in their wake foreshadowed the national struggle that would develop over Reconstruction. Moreover, the survival and resurgence of the Democratic party in New York City in the dozen years after the riots significantly influenced national events, helping to defeat the radical Republicans' agenda of racial equality.15

By 1865, the North had won the Civil War, the country was nominally reunited, and slavery was abolished nationally by the Thirteenth Amendment. The black clergyman Henry Highland Garnet, who had survived the draft riots and ministered to the wounded and homeless in his community, delivered a powerful sermon in the House of Representatives celebrating abolition and laying out the aspirations of African Americans for full citizenship and equal opportunity. However, by 1877 the Democrats, then led by the party organization in New York—most prominently, by the corporate attorney and presidential nominee Samuel Tilden, along with Marble and Wood— were able to undermine this vision and stop radical Reconstruction in its tracks. In the process, they condoned an onslaught of racial violence in the South that echoed the draft riots in its tactics and intent, and perpetuated a caste system in lieu of slavery.16

Enflamed by labor competition, the draft rioters' fury against the Emancipation Proclamation was aimed at keeping the majority of African Americans in the South while driving those in the North to the fringes of white society. Once emancipation was a legal reality, the Ku Klux Klan and similar insurgent, terrorist groups in the South sought through murder and intimidation to keep blacks from voting, to counteract the revolution in civil rights that promised to give African Americans full equality under the law.17

In this sense, the draft rioters, the Klan, and their Democratic leaders succeeded, at least in their own era. A deal struck in the contested presidential election of 1877 gave the Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes the White House in exchange for an end to Reconstruction in the South. Restoration of home rule and the withdrawal of federal troops led to almost a century of Jim Crow, of racial segregation and discrimination that arrested the social and political progress for which the radical Republicans had fought the Civil War.18

The draft riots proved to be the first outburst in what became a campaign of anti-Reconstruction racial violence—almost a century of lynching throughout the North and South aimed at suppressing the civil rights of African Americans. Not until the "second Reconstruction" of the 1950s and 1960s, when the federal government once again aggressively enforced the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, and supplemented them with new laws ensuring voting rights and desegregation of public schools, would the legislation enacted during the Civil War era truly become the basis for full racial equality under the law.19

The draft riots were also a preview of the social unrest that would afflict America well into the twentieth century. In New York, Lincoln's decision not to impose martial law left in place the corrupt Democratic machine through which "Boss" Tweed ran the city as a sort of welfare state. This was far more congenial to the poor immigrant seeking medical care or a civil service job than the Republican, Protestant establishment's vision of "scientific charity" and frugal government.* In a larger sense, however, the rioters failed, for the most part, to awaken the conscience of American government and society with regard to the deep-seated grievances of the

poor.20

Caught in the jaws of an accelerating economy dominated by industrial capitalism, American workers were exploited in the factory system and packed into the festering slums that mushroomed in an era of rapid growth and urbanization. They were free according to Republican free-labor ideology but were "wage slaves" in fact. The class conflict laid bare by the draft riots grew more acute as industrialization advanced and the gulf between rich and poor became wider during the Gilded Age. Americans reluctantly acknowledged that rigid social divisions were as much a fact of life in the United States as in European monarchies.21

One legacy of the draft riots was a harsh, repressive response to labor protests by local, state, and federal authorities, spurred by middle- and upper-class anxiety about the "dangerous classes." White workers, like African Americans, faced a long struggle to improve their lot; only gradually would they realize the benefits of joining forces with blacks instead of allowing employers and politicians to pit the two groups against each other on the bottom rung of the economic ladder.22

In a letter to his brother, Walt Whitman described the New York draft riots as "the devil's own work" but did not explicitly blame the Irish, as he might have twenty years earlier in newspaper editorials that displayed his extreme nativism, his bigotry against Irish Catholic immigrants.23George Templeton Strong's diary, by contrast, openly referred to the rioters as "Celtic devils" and tools of the Democratic party. The Republican press described the rioters as "ferocious fiends" or "human animals possessed by devils."24

Democrats, however, regarded the radical Republican agenda of emancipating the slaves, and raising them to full equality, as an infernal evil. After Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, conservative diarist Maria Daly declared that between the president and the abolitionists who influenced him, "we have not one devil, but many to contend with." Less than a year later, New York's Democratic press blamed the draft riots on the radical Republicans, saying they had provoked the working class by elevating blacks and welcoming them in white society. The New York Copperhead called Lincoln the "demon of black Republicanism."25

The Devil's Own Work

The Devil's Own Work