- Home

- Barnet Schecter

The Devil's Own Work Page 5

The Devil's Own Work Read online

Page 5

On the same day it passed the new draft law in March, Congress had authorized the suspension of habeas corpus throughout the United States, enabling the administration to detain political prisoners indefinitely without charges or any other due process of law.46 The draft law also empowered the secretary of war to create a police arm, the office of the provost marshal general, whose assistants scoured the country arresting deserters, spies, traitors, and other people deemed disloyal to the northern war effort.47†

When criticized for suspending the writ of habeas corpus, Lincoln replied that the rebels and their agents in the North were violating every other law of the land and using constitutional protections—including freedom of speech and assembly—to shield their destructive, subversive activity. Lincoln asked rhetorically, "Are all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated?"48

During the spring of 1863, Democrats had warned that Lincoln was amassing dictatorial powers, and the expanding central government was poised to wipe out what little remained of states' rights. The draft, they said, was the ultimate expression of this arbitrary federal power: The states' role of raising troops had been supplanted, and individuals—those who could not afford a substitute—were to be coerced by the distant bureaucracies in Washington into fighting and dying in an unjust war.49

In May and June, during the enrollment, Governor Seymour continued his drive to raise volunteers and forestall the draft, while predicting that it would be overturned in court. He not only asserted that the draft law was unconstitutional, but complained, rightly, that the Republican administration and its newly created Bureau of the Provost Marshal General had set disproportionately high quotas for New York City—which was predominantly Democratic. New York Republicans, including financier John Jay, branded Seymour a traitor and predicted that the governor would refuse to carry out the draft.50*

The most prominent civilian arrested by Union military authorities during the war was Ohio congressman Clement Vallandigham, a Peace Democrat running for governor, who denounced the draft, the war, and "King Lincoln" in his campaign across the state in March and April 1863. Arrested for sedition in early May, Vallandigham was denied due process and soon became a martyr for free speech in the Democratic press. Republicans watched nervously as the jailed congressman continued his campaign for both the governor's office and a peace treaty with the South.51

Along with Horatio Seymour, Manton Marble's New York World had fiercely denounced the arrest and the central government's "despotic power," even praising a mob of Vallandigham's supporters in Columbus, Ohio, who threatened to spring him from the jailhouse. "When free discussion and free voting are allowed, men are not tempted to have recourse to violence and relief of bad rulers," the World asserted. "You may stigmatize these irregular avengers as a 'mob,' but there are times when even violence is nobler than cowardly apathy."52

Lincoln resolved the immediate political crisis by commuting Vallandigham's prison sentence and banishing him to the South. Union troops turned him over to the Confederates under a flag of truce, and the warm welcome the Copperhead congressman received in the South diminished his standing with the northern public. Lincoln had won a round in convincing northerners that the enemies of the Union were cloaking themselves in the banner of civil rights. It was an ongoing struggle, however, since the uproar over Vallandigham's cause continued. In the second half of June, Lincoln issued two letters to the press, defending his vigilance against disloyalty on the home front as well as the battlefield.53

Seymour, representing the upstate Democrats known as the Albany Regency, and Marble, speaking for the wealthy urban faction nicknamed the "Swallowtails" after their fancy coats, were both careful to endorse Vallandigham's struggle for free speech but not his opposition to the war. They were not Peace Democrats like Congressman (and former mayor) Fernando Wood, who held a "Mass State Convention for Peace and Reunion" at Cooper Union in New York in June, where speakers lauded Vallandigham while denouncing the war and calling for negotiations to end the hostilities. Not only had Lincoln committed "damnable crimes against the liberty of the citizen," declared Wood, the despotic president had usurped the power of Congress by declaring war.

Wood lashed out at both the Lincoln administration and the Albany Regency, threatening the Democratic party's fragile unity. Marble faced the challenge of trying to marginalize and silence the peace men without splitting the party in two. On behalf of the state party organization, the World disavowed Wood's antiwar pronouncements. The policy of the Democratic party, Marble wrote, would be "peace and the Union but, peace or war, the Union."54

Unlike the war itself, the draft issue was an opportunity for Democratic party unity, one that had the potential to play well with the public. In the pages of the World, Marble articulated the fundamental shift of power that the draft represented in American history and daily life. In an editorial on June 9, he continued to denounce the draft and the administration by linking its infringements of civil rights with the dangers of a standing army controlled by the federal government instead of the states.

The Constitution, as well as our customs and traditions, have wisely placed the control of the militia in the hands of the local authorities. The founders of our government foresaw that a central power, having command over all the military resources of the nation, would inevitably become a despotism, and hence the people were empowered to bear arms, and the militia was recognized as a state and not a federal organization. We are now asked to give up these safeguards and hand over an unlimited military power to an administration notoriously incapable and untruthful and which has done all it dare do to subvert our free institutions.

Marble also claimed that the people were unhappy. "Already men are beginning to ask each other, To what use is this new army to be put? Is it to be employed in destroying the armed forces now waging war against the Union and the Constitution, or is it the intention of the administration to use our sons and brothers to take away our civil rights?"

In the same editorial, the World declared that "our people have become sick of useless butchery, and dread strengthening a government that is strong only with the weak and unarmed, and nerveless on the battle-field, where alone it should show its power." With this discontent "rife in the community," enforcement of the draft would be met with "manifestations of popular disaffection," Marble wrote. "It is impossible to tell what shape it will assume."55

Democratic voices began to meld on the subject of the draft. "The conscription . . . is the all-absorbing topic. Everybody talks of it; fears it as the plague, and thinks it a fraud on the body politic," a column in the Daily News—owned by Fernando Wood and edited by his brother Ben—declared in mid-June, under the ominous heading "The Beginning of the End." Noting that a provost marshal had been killed in Indiana, the writer continued: "A free people will not submit to the conscription . . . Justice must mark the course of the Administration, to avoid similar actions to that in Indiana. The life of a Provost Marshal should be respected, yet when citizens will undertake an unholy and unrighteous duty, it is difficult to control the people."56 What the Copperhead paper claimed were warnings, Republicans denounced as a steady campaign of incitement to riot.

The Daily News also introduced the element of class warfare, casting itself as the friend of the workingman, defending the longshoremen— Fernando Wood's political base—who were then on strike for wages that would supply them and their families "with the bare necessaries of life." The paper denounced the merchants who were "growing fat at the expense of their proletarian subjects," and asked, "When, oh when, will these hypocritical pharisees, clothed in purple and fine linen, be stripped of their phylacteries, and taught to respect the honest poverty of those whose distresses cry aloud to heaven against them for vengeance?"57

Thus, when Governor Seymour addressed his Fourth of July audience in New York City, he brought to a climax the crescendo of Democratic opposition to the administration that had been b

uilding during the spring and early summer. Without mentioning the upcoming draft, Seymour warned the Lincoln administration that its abuses in the name of national security could provoke a popular revolt: "Is it not revolution which you are thus creating when you say that our persons may be rightfully seized, our property confiscated, our homes entered? Are you not exposing yourselves, your own interests to as great a peril as that which you threaten us? Remember this, that the bloody and treasonable and revolutionary doctrine of public necessity can be proclaimed by a mob as well as by a government."58

The rainstorm that had prevented Meade's belated counterattack on Independence Day had also swamped the campsite of the New York militia division on its way to assist the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg. "It was well known by now, that while we were stuck in the mud on the glorious Fourth, the rebels had retreated from Gettysburg, and were now endeavoring to escape through the mountain passes," wrote militiaman George Wingate, "and we were reluctantly compelled to abandon the hopes that had been entertained of earning immortal glory, by coming in at the eleventh hour to turn their defeat into a rout."59

By 2 a.m. on July 5, the last of the Confederate troops had left the Gettysburg battlefield and by the following day had reached Hagerstown, Maryland, just six miles north of the Potomac River. The Confederate cavalry under J. E. B. Stuart was in place to protect the retreating army.

The New York militia changed course, hoping to join Meade's forces in pursuing the rebels. "On the 6th day of July, we marched till late at night, expecting to cut off the rebel wagon-train," wrote Wingate. However, the Union troops were too late. "On reaching Newman's Gap, we found that Lee's rear-guard had passed through, about eight hours before we got there."

Wingate kept his sense of humor, noting, "We were compensated by obtaining something to eat; and in addition had the pleasure of having pointed out to us, no less than six houses, in all of which Longstreet had died the previous night, and two others, where he was yet lying mortally wounded." In fact, Longstreet had survived the battle without wounds.

By July 7, Lee's army had reached Williamsport on the Potomac, but the heavy rains had raised the level of the river and the army could not cross. Lee had his troops commandeer every ferryboat in the area and shuttled the wagons of groaning, wounded men across to Virginia, but the bulk of the army was trapped on the Maryland side, waiting for the high water to recede and bracing for an attack by the Federals, Fortunately for Lee, Meade had followed cautiously, taking three days to assess his losses after the battle and treat the tens of thousands of wounded Union troops while waiting for supplies and reinforcements. Provost marshals were also busy trying to apprehend some fifteen thousand deserters who had left the army during the battle and return them to their regiments.

The Army of the Potomac finally set off after the retreating Confederates on July 7. Wingate noted that on that day, "after an unusually fatiguing march over muddy roads, rendered almost impracticable by the passage of Lee's army, the division went into camp at Funks town." After starving for most of their campaign in Pennsylvania, the militiamen were finally getting fed. "Rations had come up, and though we had to sleep on our arms for fear of attack from Stuart's cavalry, then in our neighborhood, we lay down in first rate spirits and slept the sleep of the just."

Despite the Union delays, Wingate believed that they were "pressing hard upon the heels of Lee's retreating army," but "the main army had a good deal of fight left in it still, and when it turned on its pursuers, as it frequently did, like a stag at bay, it was not to be despised." He added that because of the terrain, "the retreating army derived a great advantage over its pursuers, and were constantly enabled to take positions too strong to be attacked with less than the whole Union army and where a mere show of strength would check our advance; and then before Meade could concentrate his forces, Lee would be off."

However, Wingate also revealed how slowly the Federals moved. On July 8, when the New York militia division was annexed to a brigade of the Army of the Potomac, they were still in Pennsylvania, at Waynesboro. After resting there for three full days, these Union troops finally headed south to Maryland on the afternoon of July 11 to confront Lee's forces, waiting at Williamsport with their backs to the swollen river.

*When the Civil War began, the regular U.S. Army consisted of fewer than fifteen thousand troops, led by officers drawn from the nation's military academies. However, service in the state militia was compulsory (for men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five), and the president could call on the states to contribute their forces for up to ninety days at a time. In 1862, a new law extended the limit to nine months. Volunteers, who comprised most of the Union army's manpower, and who generally started out with even less training than the militia, were civilians whose patriotism or financial need spurred them to enlist.

*Hooker's nickname resulted from a typo, not his ferocity. A hurried battle dispatch entitled "Fighting—Joe Hooker" was transformed when a typesetter at a New York newspaper left out the dash.

*In 1864, Opdyke's political nemesis, Thurlow Weed, accused him of having "made more money out of the war by secret partnerships and contracts for army clothing, than any fifty sharpers in New York." A libel trial followed, and Weed's words were borne out. Opdyke had also manufactured guns during his term as mayor, selling them to the army at an exorbitant markup of 66 percent.

*The Academy of Music, on Fourteenth Street and Irving Place, opened in 1854 and was then the largest opera house in the world.

Tammany Hall, a patriotic society dating back to the American Revolution, was named for Chief Tamanend, a mythic warrior of the Delaware Indians. The club's hierarchy consisted of "sachems," "warriors," and "braves," and the headquarters was dubbed the "wigwam."

† in New York the Lincoln administration's political prisoners were held at Fort Lafayette, which stood close to the Brooklyn shore in the Narrows, where the eastern pier of the Verrazano Bridge now stands.

*John Jay II (1817-1894) was the grandson of the founding father.

CHAPTER 2

The Battle Lines Are Drawn:

Race, Class, and Religion

hile Lee retreated and Meade cautiously pursued in the week following Independence Day, news reports in the Northeast at last confirmed the Union victory at Gettysburg and trumpeted Grant's conquest of Vicksburg, where Confederate general John Pemberton had surrendered the fortified city on July 4. With this double victory, auspiciously occurring on the anniversary of the nation's independence, the North appeared ready to crush the rebellion, and Lincoln seemed well positioned to follow through with the draft. "The events of two days have completely altered the character of the measure and the feeling of the people in regard to it," declared James Gordon Bennett's New York Herald. "Of the three hundred thousand new levies it is probable that not one will ever be called into the field."1

However, Horace Greeley's Tribune warned that the North had to remain vigilant against a Copperhead insurrection, and he reprinted an antiadministration broadside that appeared all over the city on the eve of July 4. Signed "Spirit of '76" and containing thirteen items, the manifesto denounced the federal government as a despotic regime, a "monster smeared with the bloody sacrifice of its own children . . . Should the Confederate army capture Washington and exterminate the herd of thieves, Pharisees, and cutthroats which pasture there, defiling the temple of our liberty, we should regard it as a special interposition of Divine Providence."

Greeley cited the handbill as evidence that local Copperheads "have for months conspired and plotted to bring about a revolution in the North." Nonetheless, Greeley did not run it as front-page news on July 7 and appears to have concluded that the danger had largely passed; Meade's triumph at Gettysburg, according to Greeley, had prevented an uprising on July 4, planned to coincide with a successful Confederate invasion of the North.2

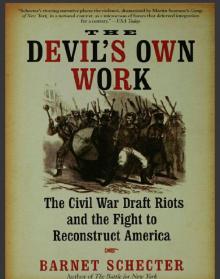

Republican cartoon: "The Copperhead Party—In Favor of a Vigorous Prosecution of Peace!"

If the Copperheads had

been defanged, class conflict remained a serious threat. When enrollment was completed and the exact dates of the upcoming draft lottery in cities and towns across the North remained a secret during the first half of July, working-class opposition reached a fever pitch. The substitution and commutation clauses of the draft law, by their apparent unfairness, seemed to strike at the heart of what was unique about America, a society free from the aristocratic hierarchies and entrenched privilege of Europe's old regimes. Americans prided themselves on living in a land of equal opportunity, both economic and social, where "every laborer is a possible gentleman."3

Republicans seemed hypocritical, denouncing slavery and celebrating the promise of social mobility in a free-labor system, while enacting the special privilege of the three-hundred-dollar clause, which enabled young entrepreneurs like J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, James Mellon, and John D. Rockefeller to procure substitutes, while cutting off the dreams of young workingmen.4

During the previous half century, urban growth and a transportation revolution (paved roads, canals, steamships, railroads) along with technological and organizational innovations (the telegraph, interchangeable machine parts, the factory system) had transformed the American economy. At the same time, the switch from preindustrial manufacturing to a capitalist system of mass production undercut the worker in relation to his employer, turning the skilled craftsman into a hired drone and aggravating the relationship between the social classes generally. The draft's exemption clause stirred up the already acute anger and insecurity of the working class, which had been mounting for decades.5

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, Thomas Jefferson had warned against the very path the country had taken. Defining freedom as economic independence, Jefferson envisioned an agricultural nation of farmers who owned their land, the source of their livelihoods. Free from the domination of a landlord or factory owner, each would make an ideal citizen in a republic. Let manufacturing and urban slums stay in Europe, Jefferson counseled. "The mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government as sores do to the strength of the human body."

The Devil's Own Work

The Devil's Own Work